Презентація на тему:

Ukrainian History of Literature. Famous Ukrainian Writers and Poets

Завантажити презентацію

Ukrainian History of Literature. Famous Ukrainian Writers and Poets

Завантажити презентаціюПрезентація по слайдам:

Урок-презентація проектної роботи в 11-му класі з теми: Ukrainian Literature. Famous Ukrainian Writers and Poets

Periods in Ukrainian literature Late Antiquity Middle Ages . Kievan Rus' Early Modern Period. Cossack Hetmanate Classicist Poetry and Prose The Ukrainian Romanticism The Ukrainian Realism The Western Ukrainian Populists And Radicals Ukrainian Modernist Writers Of The Late 19th And Early 20th century Vaplite, And The Ukrainian Cultural Renaissance Of The 1920s The Ukrainian Neoclassicists The 'Minor Renaissance' Of Ukrainian Literature In The 1940s The Artistic Ukrainian Movement “Writers Of The Sixties”

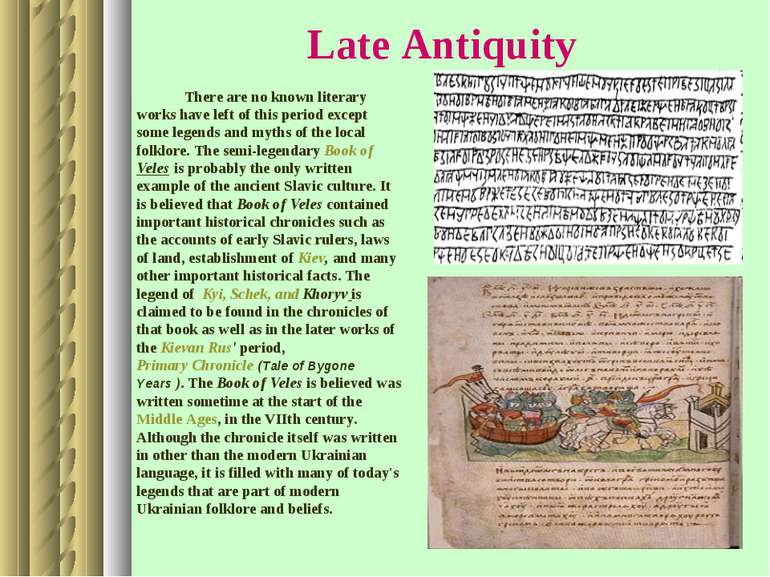

Late Antiquity There are no known literary works have left of this period except some legends and myths of the local folklore. The semi-legendary Book of Veles is probably the only written example of the ancient Slavic culture. It is believed that Book of Veles contained important historical chronicles such as the accounts of early Slavic rulers, laws of land, establishment of Kiev, and many other important historical facts. The legend of Kyi, Schek, and Khoryv is claimed to be found in the chronicles of that book as well as in the later works of the Kievan Rus' period, Primary Chronicle (Tale of Bygone Years ). The Book of Veles is believed was written sometime at the start of the Middle Ages, in the VIIth century. Although the chronicle itself was written in other than the modern Ukrainian language, it is filled with many of today's legends that are part of modern Ukrainian folklore and beliefs.

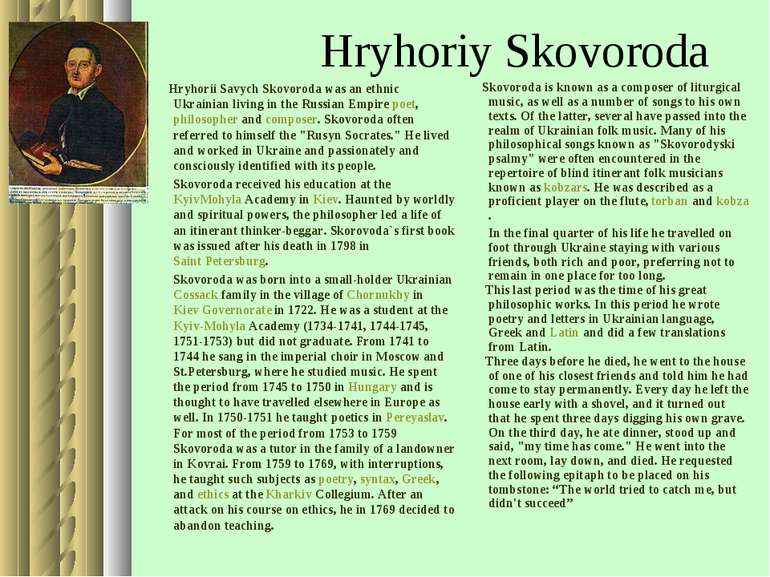

Hryhoriy Skovoroda Hryhorii Savych Skovoroda was an ethnic Ukrainian living in the Russian Empire poet, philosopher and composer. Skovoroda often referred to himself the "Rusyn Socrates." He lived and worked in Ukraine and passionately and consciously identified with its people. Skovoroda received his education at the KyivMohyla Academy in Kiev. Haunted by worldly and spiritual powers, the philosopher led a life of an itinerant thinker-beggar. Skorovoda`s first book was issued after his death in 1798 in Saint Petersburg. Skovoroda was born into a small-holder Ukrainian Cossack family in the village of Chornukhy in Kiev Governorate in 1722. He was a student at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (1734-1741, 1744-1745, 1751-1753) but did not graduate. From 1741 to 1744 he sang in the imperial choir in Moscow and St.Petersburg, where he studied music. He spent the period from 1745 to 1750 in Hungary and is thought to have travelled elsewhere in Europe as well. In 1750-1751 he taught poetics in Pereyaslav. For most of the period from 1753 to 1759 Skovoroda was a tutor in the family of a landowner in Kovrai. From 1759 to 1769, with interruptions, he taught such subjects as poetry, syntax, Greek, and ethics at the Kharkiv Collegium. After an attack on his course on ethics, he in 1769 decided to abandon teaching. Skovoroda is known as a composer of liturgical music, as well as a number of songs to his own texts. Of the latter, several have passed into the realm of Ukrainian folk music. Many of his philosophical songs known as "Skovorodyski psalmy" were often encountered in the repertoire of blind itinerant folk musicians known as kobzars. He was described as a proficient player on the flute, torban and kobza. In the final quarter of his life he travelled on foot through Ukraine staying with various friends, both rich and poor, preferring not to remain in one place for too long. This last period was the time of his great philosophic works. In this period he wrote poetry and letters in Ukrainian language, Greek and Latin and did a few translations from Latin. Three days before he died, he went to the house of one of his closest friends and told him he had come to stay permanently. Every day he left the house early with a shovel, and it turned out that he spent three days digging his own grave. On the third day, he ate dinner, stood up and said, "my time has come." He went into the next room, lay down, and died. He requested the following epitaph to be placed on his tombstone: “The world tried to catch me, but didn't succeed”

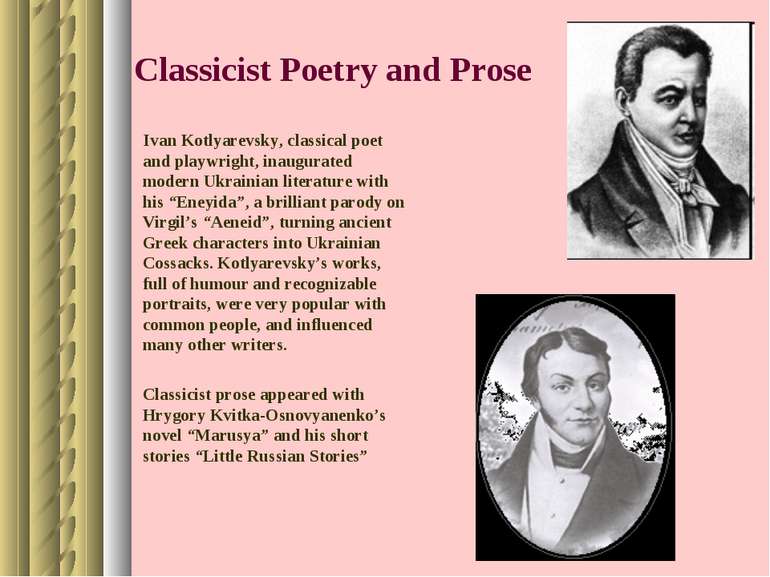

Classicist Poetry and Prose Ivan Kotlyarevsky, classical poet and playwright, inaugurated modern Ukrainian literature with his “Eneyida”, a brilliant parody on Virgil’s “Aeneid”, turning ancient Greek characters into Ukrainian Cossacks. Kotlyarevsky’s works, full of humour and recognizable portraits, were very popular with common people, and influenced many other writers. Classicist prose appeared with Hrygory Kvitka-Osnovyanenko’s novel “Marusya” and his short stories “Little Russian Stories”

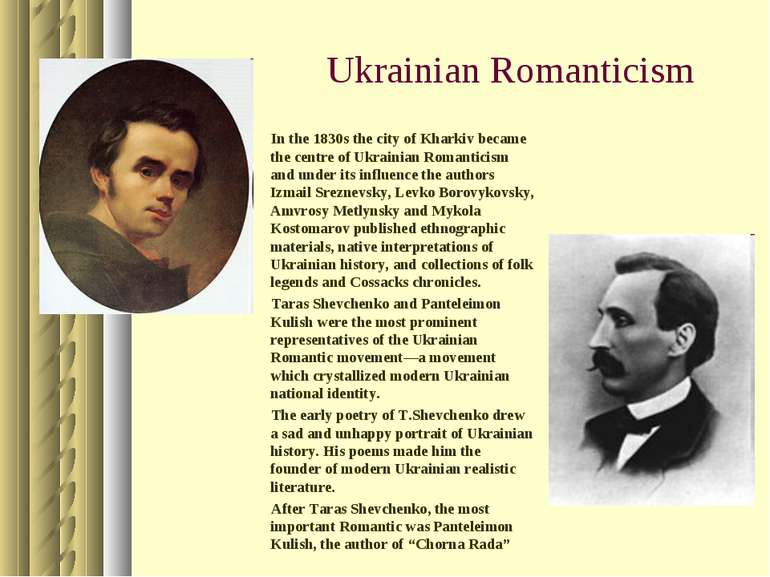

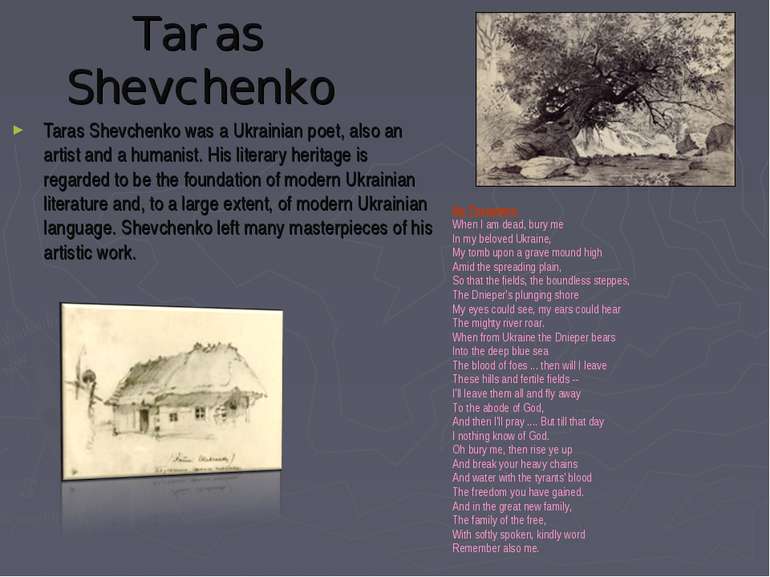

Ukrainian Romanticism In the 1830s the city of Kharkiv became the centre of Ukrainian Romanticism and under its influence the authors Izmail Sreznevsky, Levko Borovykovsky, Amvrosy Metlynsky and Mykola Kostomarov published ethnographic materials, native interpretations of Ukrainian history, and collections of folk legends and Cossacks chronicles. Taras Shevchenko and Panteleimon Kulish were the most prominent representatives of the Ukrainian Romantic movement—a movement which crystallized modern Ukrainian national identity. The early poetry of T.Shevchenko drew a sad and unhappy portrait of Ukrainian history. His poems made him the founder of modern Ukrainian realistic literature. After Taras Shevchenko, the most important Romantic was Panteleimon Kulish, the author of “Chorna Rada”

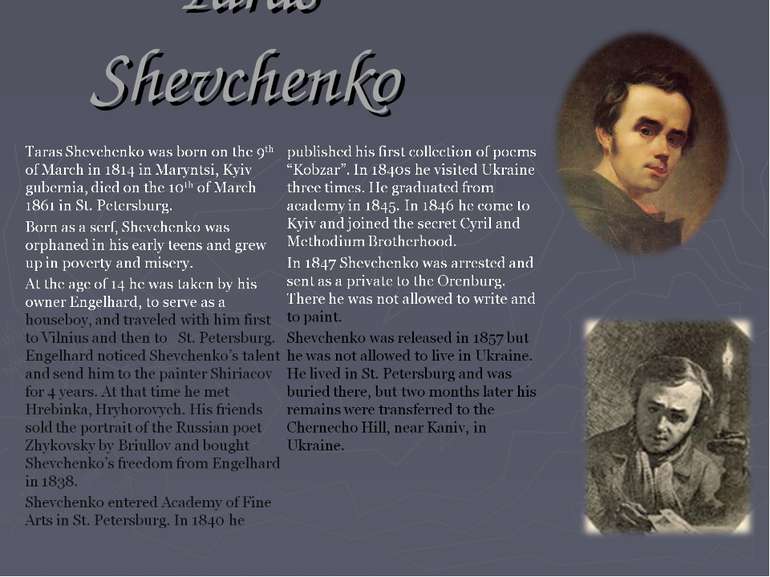

Taras Shevchenko Taras Shevchenko was a Ukrainian poet, also an artist and a humanist. His literary heritage is regarded to be the foundation of modern Ukrainian literature and, to a large extent, of modern Ukrainian language. Shevchenko left many masterpieces of his artistic work. My Testament When I am dead, bury me In my beloved Ukraine, My tomb upon a grave mound high Amid the spreading plain, So that the fields, the boundless steppes, The Dnieper's plunging shore My eyes could see, my ears could hear The mighty river roar. When from Ukraine the Dnieper bears Into the deep blue sea The blood of foes ... then will I leave These hills and fertile fields -- I'll leave them all and fly away To the abode of God, And then I'll pray .... But till that day I nothing know of God. Oh bury me, then rise ye up And break your heavy chains And water with the tyrants' blood The freedom you have gained. And in the great new family, The family of the free, With softly spoken, kindly word Remember also me.

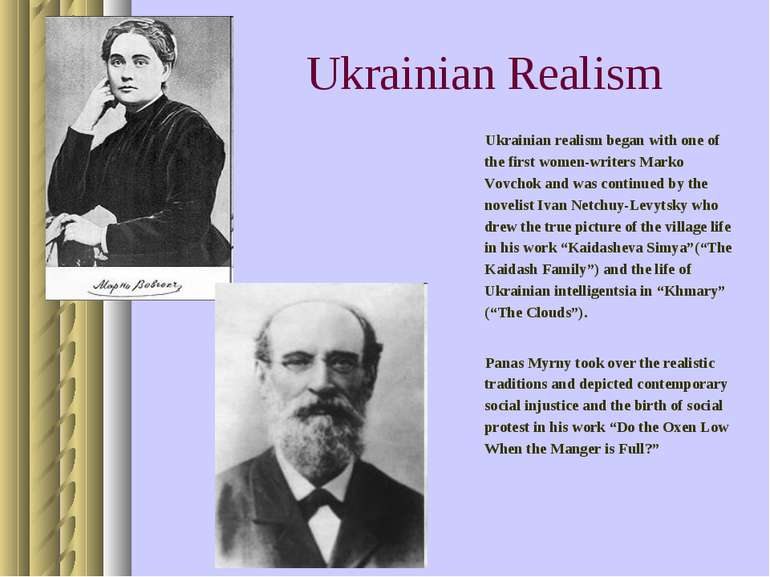

Ukrainian Realism Ukrainian realism began with one of the first women-writers Marko Vovchok and was continued by the novelist Ivan Netchuy-Levytsky who drew the true picture of the village life in his work “Kaidasheva Simya”(“The Kaidash Family”) and the life of Ukrainian intelligentsia in “Khmary” (“The Clouds”). Panas Myrny took over the realistic traditions and depicted contemporary social injustice and the birth of social protest in his work “Do the Oxen Low When the Manger is Full?”

The Western Ukrainian Populists and Radicals Like Taras Shevchenko, Ivan Franko is considered one of Ukraine's most important literary figures. A very prolific writer, poet, publicist, and important political leader, Franko exerted a tremendous influence not only on his native Western Ukraine, but on the Ukrainian culture and national consciousness as a whole. In the last decades of the 19th-century and the first decades of the 20th-century he played a key role in the shaping of the powerful Western Ukrainian populist movement and the formation of Ukrainian radicalism. Although he was an ardent proponent of the realist style in literature and art and was consistently critical of modernist trends, Franko himself did not remain immune to new literary currents and produced (in such collections as Withered Leaves, 1896) one of the first modernist poems in Western Ukraine.

Ivan Franko Ivan Franko August 27, 1856, pp. Naguevichi, Drohobych county, Galicia - May 28, 1916, Lviv) - Ukrainian writer, poet, novelist, scholar, journalist and leader of the revolutionary socialist movement in Galicia (Austro-Hungarian Empire). One of the initiators of the reasons the Russian-Ukrainian Radical Party, which operated on the territory of Austria.

Ivan Franco was born August 27 1856r. in the village Nahuievychi Drogobycheskogo County in eastern Galicia, near Borislav, family farmer-blacksmith. Franco always spoke of himself as "son of a peasant, peasant. His father, a blacksmith, earning not only his own family, but also on all relatives, he would give his son a good education. Mother of Ivan Franco - Maria Jerzy derived from the dilapidated Polish nobility. It was not exactly a poor peasant family. He studied first at the school in the village Yasenytsya-Light (1862-1864), then the so-called normal school at the Basilian Monastery in Drohobych (1864-1867). In 1875 he graduated from high school in Drohobych. In many stories (Gritseva school science "," Pencil ") transferred certain artistic moments from this season of life of the author., How hard it was even gifted peasant boy that lost his ninth year his father, his closest adviser, to acquire education .He had to live in an apartment in the distant relative on the outskirts Drogobycha often sleep in coffins, which were made in its joinery (in carpentry). Studiing in the Gymnasium, Franco showed phenomenal skills: could almost literally repeat comrades information that serving teachers in the classroom, deeply zasvoyuvav content of books read. And read a lot: the works of European classics, kultorolohichni, istoriosofski labor, popular books on natural themes.

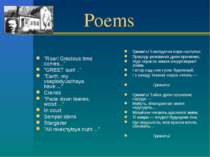

Poems "Roar! Gracious time comes..." "GREET sun! .." "Earth, my vseplodyuschaya have ...“ Cranes "Pade down leaves, wood ...“ In court Semper idemi Stargazer "All nivechytsya truth ..." Гримить! Благодатна пора наступає, Природу розкішная дрож пронимає, Жде спрагла земля плодотворної зливи, І вітер над нею гуляє бурхливий, І з заходу темная хмара летить — Гримить! Гримить! Тайна дрож пронимає народи, — Мабуть, благодатная хвиля надходить… Мільйони чекають щасливої зміни, Ті хмари — плідної будущини тіни, Що людськість, мов красна весна, обновить… Гримить!

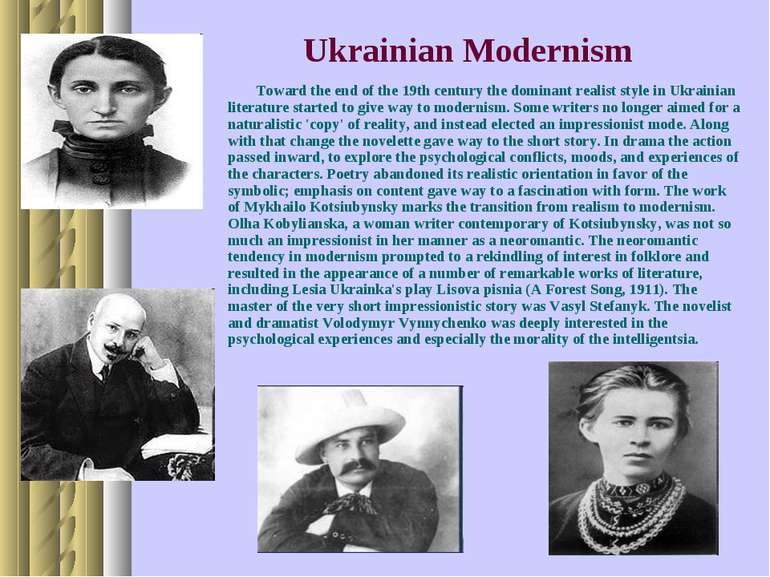

Ukrainian Modernism Toward the end of the 19th century the dominant realist style in Ukrainian literature started to give way to modernism. Some writers no longer aimed for a naturalistic 'copy' of reality, and instead elected an impressionist mode. Along with that change the novelette gave way to the short story. In drama the action passed inward, to explore the psychological conflicts, moods, and experiences of the characters. Poetry abandoned its realistic orientation in favor of the symbolic; emphasis on content gave way to a fascination with form. The work of Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky marks the transition from realism to modernism. Olha Kobylianska, a woman writer contemporary of Kotsiubynsky, was not so much an impressionist in her manner as a neoromantic. The neoromantic tendency in modernism prompted to a rekindling of interest in folklore and resulted in the appearance of a number of remarkable works of literature, including Lesia Ukrainka's play Lisova pisnia (A Forest Song, 1911). The master of the very short impressionistic story was Vasyl Stefanyk. The novelist and dramatist Volodymyr Vynnychenko was deeply interested in the psychological experiences and especially the morality of the intelligentsia.

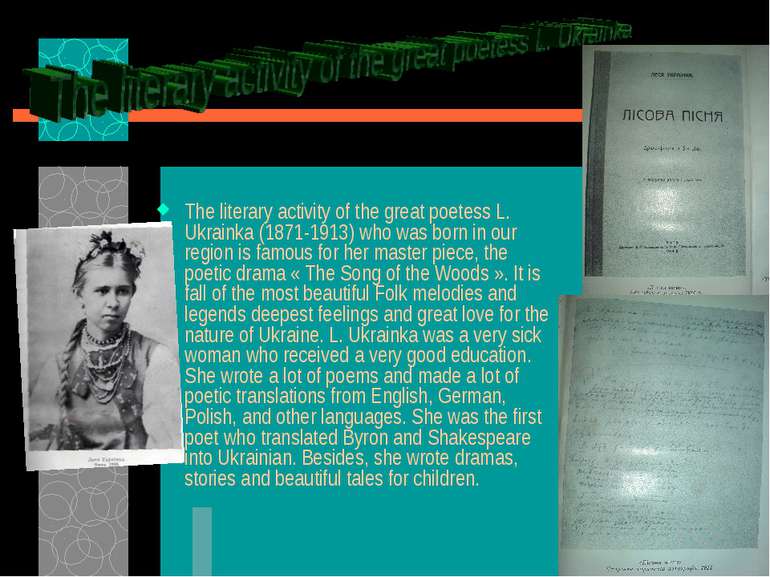

One of the great Ukrainian poetesses is Lesia Ukrainka. However, Lesia Ukrainka isn't a real name of the outstanding poetess. Under this penname Larysa Kosach entered the world of literature and became renowned all over the world. Lesia Ukrainka was born on 25 February 1871 in Novohrad-Volyns'kyi, and she was the second child in the family. Her father Petro Antonovych Kosach was a progressive person for his time. Her mother was a famous Ukrainian writer Olena Pchilka. Lesia Ukrainka spent her childhood in the village of Kolodiazhne. In 1881, in Luts'k she had wet feet in the icy water. The doctor diagnosed her disease as tuberculosis of bones. It meant that her dream to become a pianist was ruined. All her life the illness drove her from clinic to clinic, from country to country. Unlike other people, who travelled to see exotic lands, Lesia Ukrainka took her foreign trips as a bitter necessity, which often drained her off the last century

The literary activity of the great poetess L. Ukrainka (1871-1913) who was born in our region is famous for her master piece, the poetic drama « The Song of the Woods ». It is fall of the most beautiful Folk melodies and legends deepest feelings and great love for the nature of Ukraine. L. Ukrainka was a very sick woman who received a very good education. She wrote a lot of poems and made a lot of poetic translations from English, German, Polish, and other languages. She was the first poet who translated Byron and Shakespeare into Ukrainian. Besides, she wrote dramas, stories and beautiful tales for children.

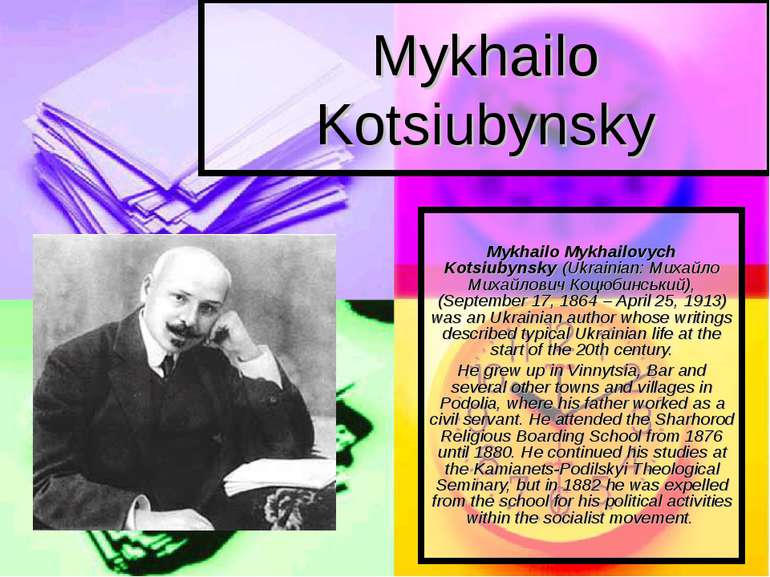

Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky Mykhailo Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky (Ukrainian: Михайло Михайлович Коцюбинський), (September 17, 1864 – April 25, 1913) was an Ukrainian author whose writings described typical Ukrainian life at the start of the 20th century. He grew up in Vinnytsia, Bar and several other towns and villages in Podolia, where his father worked as a civil servant. He attended the Sharhorod Religious Boarding School from 1876 until 1880. He continued his studies at the Kamianets-Podilskyi Theological Seminary, but in 1882 he was expelled from the school for his political activities within the socialist movement.

His life From 1888 to 1890, he was a member of the Vinnytsia Municipal Duma. In 1890, he visited Galicia, where he met several other Ukrainian cultural figures including Ivan Franko and Volodymyr Hnatiuk. It was there in Lviv that his first story Nasha Khatka (Ukrainian: Наша хатка) was published. During this period, he worked as a private tutor in and near Vinnytsia. There, he could study life in traditional Ukrainian villages, which was something he often came back to in his stories including the 1891 Na Viru and the 1901 Dorohoiu tsinoiu He moved to Chernihiv in 1898 where he worked as a statistician at the statistics bureau of the Chernihiv zemstvo. He also was active in the Chernigov Governorate Scholarly Archival Commission and headed the Chernihiv Prosvita society from 1906 to 1908.

Family In January 1896, he married Vira Ustymivna Kotsiubynska (1863-1921). His son, Yuriy Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky (1896–1937), was a bolshevik and a Red Army commander during the 1917–1921 Civil War. Later, he held several high positions within the Communist Party of Ukraine, but in 1935, he was expelled from the party. In October 1936, he was accused of having counter-revolutionary contacts and together with other bolsheviks have organized a Ukrainian Trotskyist Centre. The year after, he was sentenced to death and executed. He was rehabilitated in 1955.

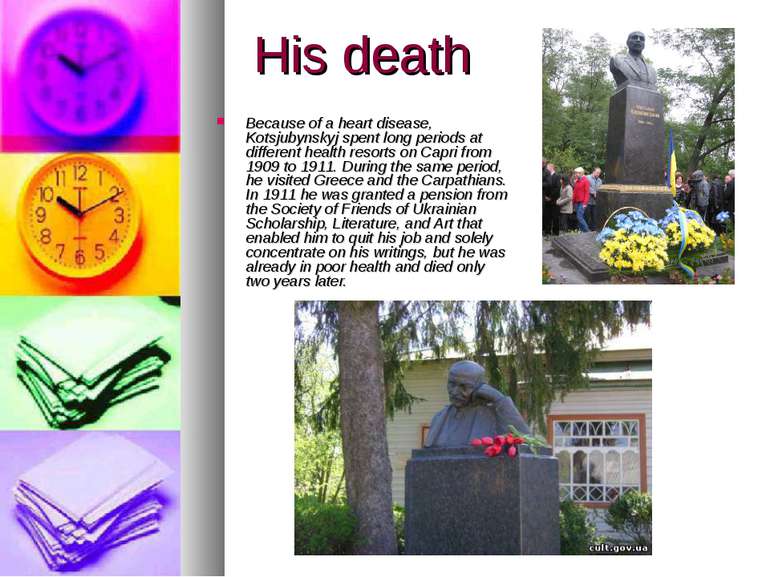

His death Because of a heart disease, Kotsjubynskyj spent long periods at different health resorts on Capri from 1909 to 1911. During the same period, he visited Greece and the Carpathians. In 1911 he was granted a pension from the Society of Friends of Ukrainian Scholarship, Literature, and Art that enabled him to quit his job and solely concentrate on his writings, but he was already in poor health and died only two years later.

Ukrainian Cultural Renaissance of the 1920s In the first three decades of the 20th century, Ukrainian literature experienced a renaissance. Different literary movements quickly changed each other or lived side by side and competed with each other. Realism with a decadent strain was characteristic of Volodymyr Vynnychenko’s prose. Pavlo Tychina was a leading Symbolist poet. Neoclassicism produced outstanding poets in Mykola Zerov and Maksym Rylsky. Futurism was represented by one of the greatest 20th century Ukrainian poets Mykola Bazhan. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, until 1932 Ukrainian literature experienced relative freedom. Many new literary groups and organizations were formed, young writers’ works were published, new magazines appeared. The books of Mykola Kulish, Mykola Hvylyoviy, Hryhory Kosynka, Yury Yanovsky, Oleksander Dovzhenko, Ostap Vyshnya and many other Ukrainian writers and poets were popular among common people. In 1932 the Communist Party began enforcing Socialist Realism as the required literary style. Its typical representatives became Oleksander Korniychuk and Mykhaylo Stelmach. The others who did not follow the directive of the Party were repressed. It is believed that during that period 250 Ukrainian writers were imprisoned, exciled or executed. But despite the repressions Ukrainian literature gave the world such outstanding writers as Oles Honchar and Oleksander Dovzhenko.

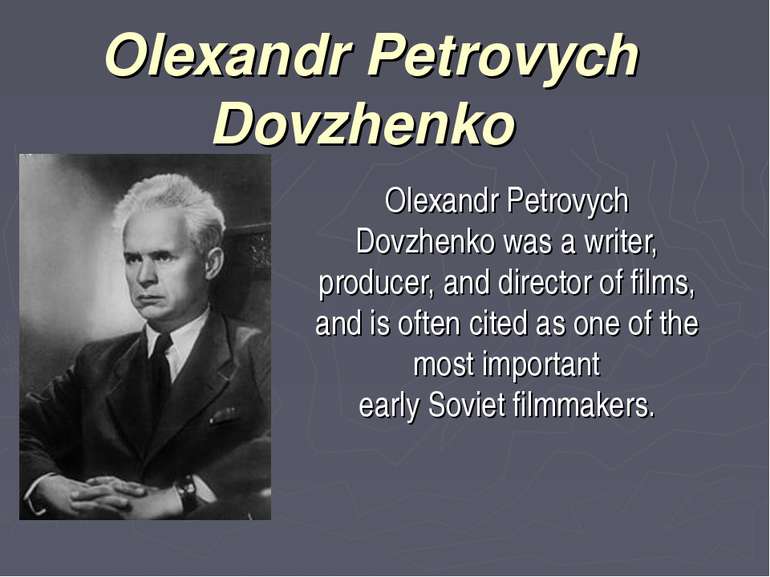

Olexandr Petrovych Dovzhenko Olexandr Petrovych Dovzhenko was a writer, producer, and director of films, and is often cited as one of the most important early Soviet filmmakers.

Olexandr Dovzhenko(1894 -1956) was born in the district of Viunyshche in Sosnytsia, a townlet in the Chernihiv oblast of present-day Ukraine (at the time a part of Imperial Russia) His relatives: Petro Semenovych Dovzhenko and Odarka Ermolaivna Dovzhenko His most famous novels: “Zacharovana Desna”, “Ukarina u ogni” He served as a wartime journalist for the Red Army during World War II, Dovzhenko began to feel ever more oppressed by the bureaucracy of Stalin's Soviet Union. After spending several years writing, co-writing, and producing films at Mosfilm Studios in Moscow, he turned to writing novels. Over a 20-year career, Dovzhenko personally directed only seven films. Dovzhenko died of a heart attack on November 25, 1956 in Moscow.

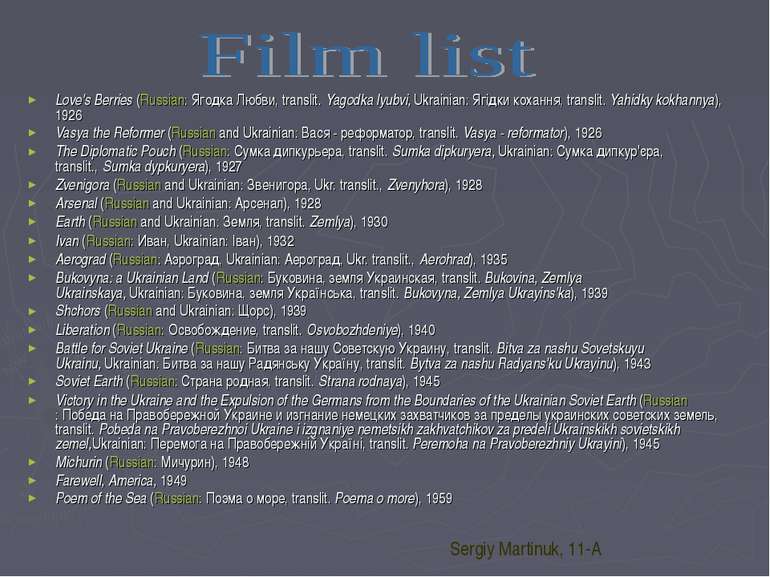

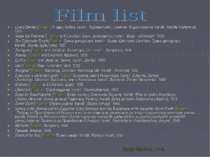

Love's Berries (Russian: Ягoдка Любви, translit. Yagodka lyubvi, Ukrainian: Ягідки кохання, translit. Yahidky kokhannya), 1926 Vasya the Reformer (Russian and Ukrainian: Вася - реформатор, translit. Vasya - reformator), 1926 The Diplomatic Pouch (Russian: Сумка дипкурьера, translit. Sumka dipkuryera, Ukrainian: Сумка дипкур'єра, translit., Sumka dypkuryera), 1927 Zvenigora (Russian and Ukrainian: Звенигора, Ukr. translit., Zvenyhora), 1928 Arsenal (Russian and Ukrainian: Арсенал), 1928 Earth (Russian and Ukrainian: Зeмля, translit. Zemlya), 1930 Ivan (Russian: Ивaн, Ukrainian: Iвaн), 1932 Aerograd (Russian: Аэроград, Ukrainian: Аероград, Ukr. translit., Aerohrad), 1935 Bukovyna: a Ukrainian Land (Russian: Буковина, земля Украинская, translit. Bukovina, Zemlya Ukrainskaya, Ukrainian: Буковина, зeмля Українськa, translit. Bukovyna, Zemlya Ukrayins'ka), 1939 Shchors (Russian and Ukrainian: Щopc), 1939 Liberation (Russian: Освобождение, translit. Osvobozhdeniye), 1940 Battle for Soviet Ukraine (Russian: Битва за нашу Советскую Украину, translit. Bitva za nashu Sovetskuyu Ukrainu, Ukrainian: Битва за нашу Радянську Україну, translit. Bytva za nashu Radyans'ku Ukrayinu), 1943 Soviet Earth (Russian: Cтpaнa poднaя, translit. Strana rodnaya), 1945 Victory in the Ukraine and the Expulsion of the Germans from the Boundaries of the Ukrainian Soviet Earth (Russian: Победа на Правобережной Украине и изгнание немецких захватчиков за пределы украинских советских земель, translit. Pobeda na Pravoberezhnoi Ukraine i izgnaniye nemetsikh zakhvatchikov za predeli Ukrainskikh sovietskikh zemel,Ukrainian: Перемога на Правобережній Україні, translit. Peremoha na Pravoberezhniy Ukrayini), 1945 Michurin (Russian: Мичурин), 1948 Farewell, America, 1949 Poem of the Sea (Russian: Поэма о море, translit. Poema o more), 1959 Sergiy Martinuk, 11-A

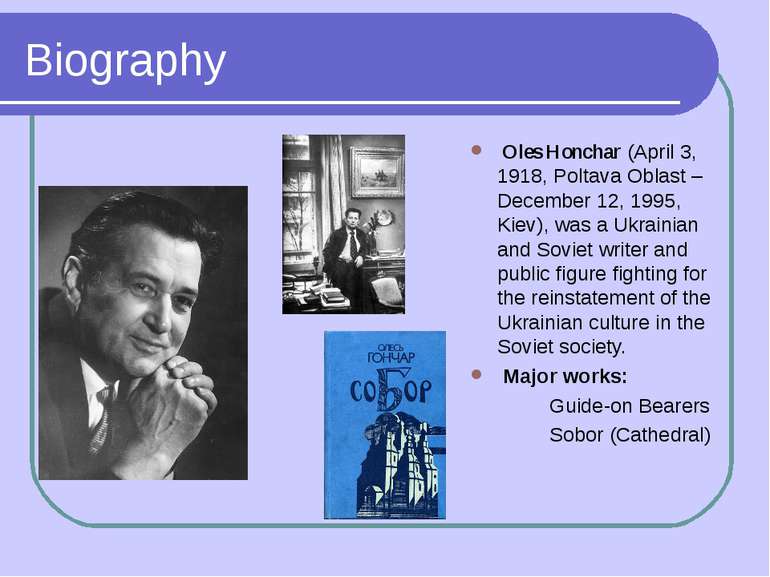

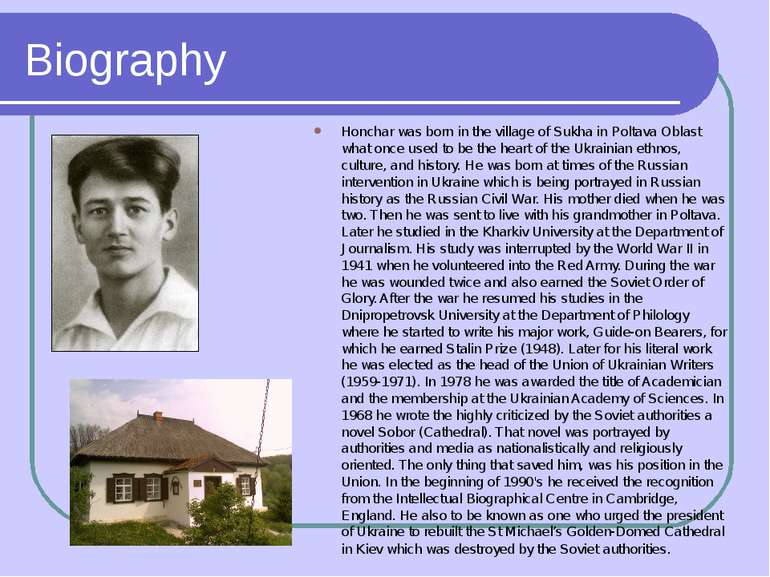

Biography Oles Honchar (April 3, 1918, Poltava Oblast – December 12, 1995, Kiev), was a Ukrainian and Soviet writer and public figure fighting for the reinstatement of the Ukrainian culture in the Soviet society. Major works: Guide-on Bearers Sobor (Cathedral)

Biography Honchar was born in the village of Sukha in Poltava Oblast what once used to be the heart of the Ukrainian ethnos, culture, and history. He was born at times of the Russian intervention in Ukraine which is being portrayed in Russian history as the Russian Civil War. His mother died when he was two. Then he was sent to live with his grandmother in Poltava. Later he studied in the Kharkiv University at the Department of Journalism. His study was interrupted by the World War II in 1941 when he volunteered into the Red Army. During the war he was wounded twice and also earned the Soviet Order of Glory. After the war he resumed his studies in the Dnipropetrovsk University at the Department of Philology where he started to write his major work, Guide-on Bearers, for which he earned Stalin Prize (1948). Later for his literal work he was elected as the head of the Union of Ukrainian Writers (1959-1971). In 1978 he was awarded the title of Academician and the membership at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. In 1968 he wrote the highly criticized by the Soviet authorities a novel Sobor (Cathedral). That novel was portrayed by authorities and media as nationalistically and religiously oriented. The only thing that saved him, was his position in the Union. In the beginning of 1990's he received the recognition from the Intellectual Biographical Centre in Cambridge, England. He also to be known as one who urged the president of Ukraine to rebuilt the St Michael’s Golden-Domed Cathedral in Kiev which was destroyed by the Soviet authorities.

Biography Oles Honchar was a Hero of Socialist Labor (1978), laureate of Stalin Prize (1948 and 1949), laureate of Lenin Prize (1964), laureate of the USSR State Prize (1982) laureate of the Shevchenko National Prize (1962), member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union since 1946, candidate to the members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union since 1971

Ostap Vyshnya (1889-1956) Ostap Vyshnya (real name Pavlo Hubenko, 13 November 1889- 28 September 1956) was a Ukrainian writer, humourist and satirist. Early life Pavlo Hubenko was born on 13 November 1889 in Chechva Settlement (in Sunny Oblast) not far from Hrun’ (now a village in Poltava oblast) in a large peasant family of 17 children. Career and repression The first printed story by Ostap Vyshnya – “Denikin’s Democratic Reforms” was published on 2 November 1919 in the newspaper “Narodna Volia” under the pen name “P.Hrunsky”. Several satirical articles were also printed in this name newspaper by the young writer, and from April 1921, when he had become a journalist with the government newspaper, began the period of his creative activity and regular articles in the press. The pen name of “Ostap Vyshnya” appeared for the first time on 22 July 1921. Death Ostap Vyshnya died on 28 September 1956 in Kyiv.

Pavlo Tychina Pavlo Tychyna was born on 27 January 1891 in Pisky, Kozelets county, Chernihiv gubernia, died 16 September 1967 in Kyiv. Poet; recipient of the highest Soviet awards and orders; member of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR (now NANU) from 1929; deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR from 1938 and its chairman in 1953–9; deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR from 1946; director of the Institute of Literature of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR in 1936–9 and 1941–3; and minister of education of the Ukrainian SSR in 1943–8. He graduated from the Chernihiv Theological Seminary in 1913. His first poems were in part influenced by Oleksander Oles, Mykola Vorony, and Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. His first extant poem is dated 1906 (‘Synie nebo zakrylosia’ [The Blue Sky Closed]), and the first one published (‘Vy znaiete, iak lypa shelestyt'?’ [You Know How the Linden Rustles?]) appeared in in 1912. In 1913 Tychyna enrolled at the Kyiv Commercial Institute, and while a student, he worked on the editorial boards of the newspapers Rada (Kyiv) and Svitlo .Later he worked for the Chernihiv zemstvo administration. His first collection of poetry, Soniashni kliarnety (Clarinets of the Sun, 1918), is a programmatic work, in which he created a uniquely Ukrainian form of symbolism and established his own poetic style, known as kliarnetyzm (clarinetism). In 1923 he moved to Kharkiv and joined the organization Hart and, in 1927, Vaplite. His membership in the latter organization and his poem ‘Chystyla maty kartopliu’ (Mother Was Peeling Potatoes) provoked harsh official criticism, and he was accused of ‘bourgeois nationalism.’ Soon after, Tychyna capitulated to the Soviet regime and began producing collections of poetry in the socialist-realist style sanctioned by the Party. They included Chernihiv (1931) and Partiia vede (The Party Leads, 1934). The latter collection has symbolized the submission of Ukrainian writers to Stalinism. The Second World War intensified those features of Tychyna's poetry. Tychyna did not take part in the Ukrainian cultural revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s, and he even attacked the shistdesiatnyky. The poetry of the last decade before his death is full of glorification of the Party, of the new leader, Nikita Khrushchev, and of heroes of socialist labor, collective farms, and so on.

VolodYmYr Sosyura Volodymyr Sosyura (born January 6, 1898 in Debaltseve, in the Yekaterinoslav Governorate (today Donbas region) - died January 8, 1965 in Kiev) was a Ukrainian lyric poet. Sosyura fought in Petliura's Ukrainian People's Army during the winter of 1918 to the autumn of 1919, before being taken prisoner by Denikin's Volunteer Army. He was sentenced to death, but managed to escape. Later, after the UPR was overrun, he joined the Red Army. After the Russian Civil War in Ukraine ended he studied at the Artem Communist University in Kharkiv from 1922-23, then at the workers' faculty of the Public Education Institute (Kharkiv) from 1923-25. Sosyura belonged to the Ukrianian literary organizations Pluh, Hart, VAPLITE, and the All-Ukrainian Association of Proletarian Writers. In the 1920s-30s Sosyura became very popular, but his ideological loyalties were torn between patriotic feelings for Ukraine and those for the Soviet Union and its often-changing ideologies. Even though he had long been a member of the CPU(b), he was frequently in conflict with it, and was twice expelled for “nationalistic undertones,” he was even forced to undergo a “reeducation” at a factory in 1930-1931. Many of Sosyura's poems were not published. In 1948 he was awarded the highest honors of the Stalin Prize, but then he came under harsh criticism for his poem entitled Love Ukraine (Любіть Україну), which was deemed too nationalistic in its tone by several Soviet news-media including Pravda. Afterwards his wife was arrested and spent six years in NKVD prisons. Sosyura died in Kiev at the age of 66.

2007 Ukrainian literary accidentally found a previously unknown poem by Vladimir Sosyuri in the newspaper "peasant community" of August 3, 1919 titled "The Last Battle." Vasylko Spring Garden Anna Ivanovna Brothers Had not broken the ice on the Dnipro Winter When svitalo Love Ukraine Summer Mazeppa Mary Autumn So nobody loved Teacher Boy Red Winter I remember

Poems Люблю дивитись на Дніпро я З його стрімких , високих круч , коли здається , що рукою Торкнутись можеш ти до туч . Синіє даль за далиною , поля , гаї , озер комиш … І все летить перед тобою , і ти , здається , сам летиш … І все , як пісня соловїна , чуття загострює моє … Прекрасна мить , коли людина , людина птицею стає !

Love Ukraine Love Ukraine, like sun that you love Like wind, like grass, and like water, Whenever you're happy, in moments of gladness, At times of trouble, do love. Love Ukraine when asleep or awake The glamourous your Ukraine The beauty of it, always alive and new And language of hers full of charm. Amongst the brother-made nations, like garden in dew She shines through the ages again Love Ukraine with all of your heart And all of the deeds that you make...

The Artistic Ukrainian Movement The Artistic Ukrainian Movement (Mystetskyi ukrainskyi rukh). An artistic-literary organization of Ukrainian emigres in Europe. It was founded on 25 September 1945 in Furth, Germany, on the initiative of a committee consisting of Ivan Bahriany, V. Domontovych (Viktor Petrov), Yurii Kosach, Ihor Kostetsky, Ivan Maistrenko, and Yu. Sherekh (George Yurii Shevelov). MUR organized three writers' congresses (1945, 1947, and 1948) as well as three conferences devoted to various aspects of literary activity. The head of the organization during its whole duration was Ulas Samchuk, and its membership numbered 61. The objectives of MUR were to gather Ukrainian writers scattered by the Second World War, to organize the publication of their works, and to become a center for creative dialogues among members representing various styles and literary aims. MUR managed to organize almost all of the noted emigre writers and provide them with a forum for discussion while it stimulated an interest in literature among the public at large.

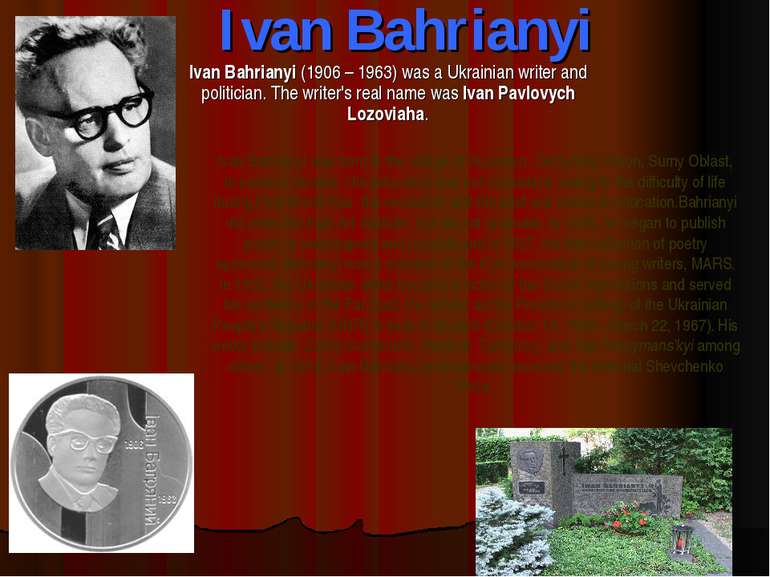

Ivan Bahrianyi Ivan Bahrianyi (1906 – 1963) was a Ukrainian writer and politician. The writer's real name was Ivan Pavlovych Lozoviaha. Ivan Bahrianyi was born in the village of Kuzemyn, Okhtyrskyi Raion, Sumy Oblast, in eastern Ukraine. His education was not consistent, owing to the difficulty of life during First World War, the revolution and the post-war chaos in education.Bahrianyi did enter the Kyiv Art Institute, but did not graduate. In 1926, he began to publish poetry in newspapers and journals and in 1927, his first collection of poetry appeared. Bahrianyi was a member of the Kyiv association of young writers, MARS. In 1932, the Ukrainian writer became a victim of the Soviet repressions and served his sentence in the Far East. He served as the President (acting) of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) in exile in Munich (October 19, 1965 - March 22, 1967). His works include: Zolotyi bumeranh, Heneral, Tuhrolovy, and Sad Hetsymans'kyi among others. In 1992, Ivan Bahrianyi posthumously received the national Shevchenko Prize.

“Writers of the Sixties” The post-Stalinist period saw the birth of a new generation of Ukrainian writers, known as the “Writers of the Sixties” who rejected Socialist Realism. Their ranks included Vasyl Stus, Lina Kostenko, Vasyl Simonenko, Vitaly Korotych, Yevhen Hutsalo, Hryhir Tiutiunnyk, Ivan Drach and some others. Representative measures taken in the 1970s silenced many of them who either turned back to the approved style or were driven from the country.

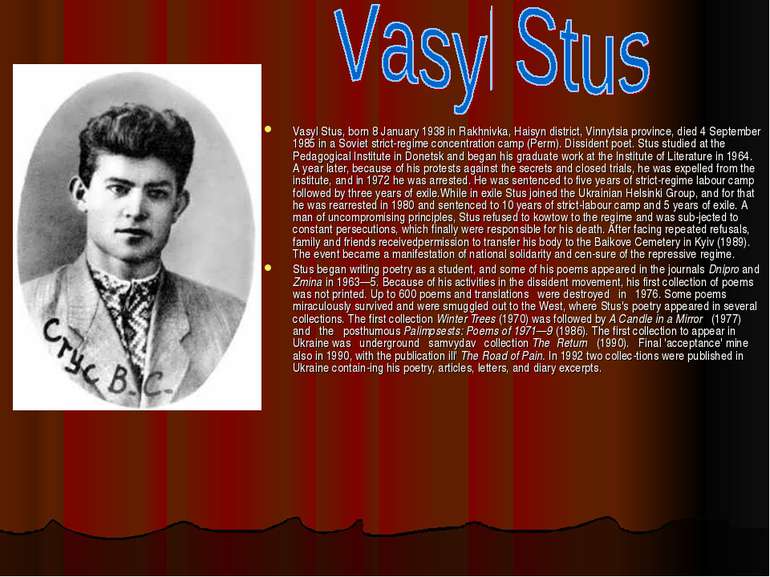

Vasyl Stus, born 8 January 1938 in Rakhnivka, Haisyn district, Vinnytsia province, died 4 September 1985 in a Soviet strict-regime concentration camp (Perm). Dissident poet. Stus studied at the Pedagogical Institute in Donetsk and began his graduate work at the Institute of Literature in 1964. A year later, because of his protests against the secrets and closed trials, he was expelled from the institute, and in 1972 he was arrested. He was sentenced to five years of strict-regime labour camp followed by three years of exile.While in exile Stus joined the Ukrainian Helsinki Group, and for that he was rearrested in 1980 and sentenced to 10 years of strict-labour camp and 5 years of exile. A man of uncompromising principles, Stus refused to kowtow to the regime and was sub jected to constant persecutions, which finally were responsible for his death. After facing repeated refusals, family and friends receivedpermission to transfer his body to the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv (1989). The event became a manifestation of national solidarity and cen sure of the repressive regime. Stus began writing poetry as a student, and some of his poems appeared in the journals Dnipro and Zmina in 1963—5. Because of his activities in the dissident movement, his first collection of poems was not printed. Up to 600 poems and translations were destroyed in 1976. Some poems miraculously survived and were smuggled out to the West, where Stus's poetry appeared in several collections. The first collection Winter Trees (1970) was followed by A Candle in a Mirror (1977) and the posthumous Palimpsests: Poems of 1971—9 (1986). The first collection to appear in Ukraine was underground samvydav collection The Return (1990). Final 'acceptance' mine also in 1990, with the publication ill' The Road of Pain. In 1992 two collec tions were published in Ukraine contain ing his poetry, articles, letters, and diary excerpts.

Burst into spring, my soul, and do not wail. A frost of white Ukraine's bright sun is palling. Go, seek the guelder rose's shadow fallen on the black waters — seek the red shadow's trail where there are few of us. A cluster small. Only for prayers and hopes expressed in sighing. We all are doomed to an untimely dying. For crimson blood is sharp as any gall, it stings as if within our veins forever in a grey whirlwind of lamenting, twist clusters of pain which fall in the abyss, and, in undying woe, tumble together. Vasyl Stus

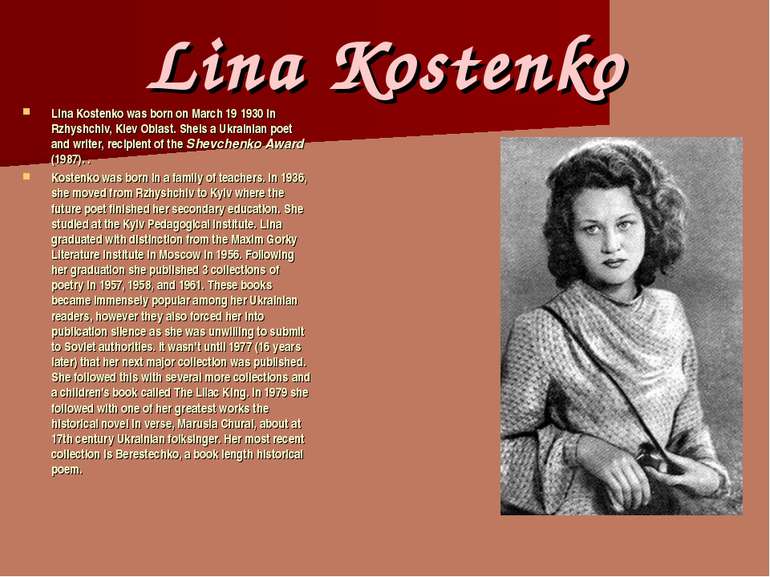

Lina Kostenko Lina Kostenko was born on March 19 1930 in Rzhyshchiv, Kiev Oblast. Sheis a Ukrainian poet and writer, recipient of the Shevchenko Award (1987). . Kostenko was born in a family of teachers. In 1936, she moved from Rzhyshchiv to Kyiv where the future poet finished her secondary education. She studied at the Kyiv Pedagogical Institute. Lina graduated with distinction from the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute in Moscow in 1956. Following her graduation she published 3 collections of poetry in 1957, 1958, and 1961. These books became immensely popular among her Ukrainian readers, however they also forced her into publication silence as she was unwilling to submit to Soviet authorities. It wasn't until 1977 (16 years later) that her next major collection was published. She followed this with several more collections and a children's book called The Lilac King. In 1979 she followed with one of her greatest works the historical novel in verse, Marusia Churai, about at 17th century Ukrainian folksinger. Her most recent collection is Berestechko, a book length historical poem.

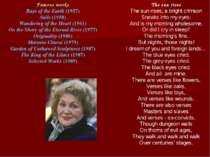

Famous works Rays of the Earth (1957) Sails (1958) Wandering of the Heart (1961) On the Shore of the Eternal River (1977) Originality (1980) Marusia Churai (1979) Garden of Unthawed Sculptures (1987) The King of the Lilacs (1987) Selected Works (1989) The sun rises The sun rises; a bright crimson Sneaks into my eyes: And is my morning wholesome, Or did I cry in sleep? The morning’s fine. But nights, those nights! I dream of you and foreign lands… The blue eyes cried. The grey eyes cried. The black eyes cried. And all- are mine. There are verses like flowers, Verses like oaks, Verses like toys, And verses like wounds. There are also verses Masters and slaves And verses - ex-convicts. Though dungeon walls On thorns of evil ages, They walk and walk and walk Over centuries’ stages.

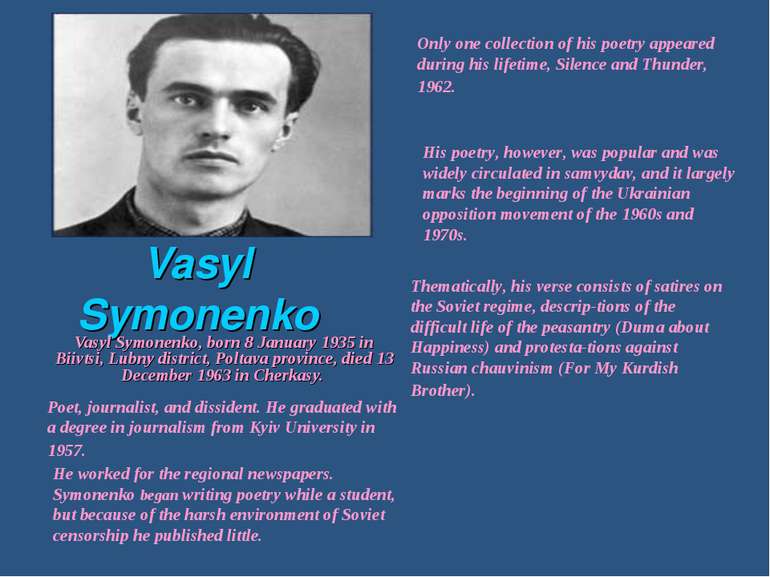

Vasyl Symonenko Vasyl Symonenko, born 8 January 1935 in Biivtsi, Lubny district, Poltava province, died 13 December 1963 in Cherkasy. His poetry, however, was popular and was widely circulated in samvydav, and it largely marks the beginning of the Ukrainian opposition movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Thematically, his verse consists of satires on the Soviet regime, descrip tions of the difficult life of the peasantry (Duma about Happiness) and protesta tions against Russian chauvinism (For My Kurdish Brother). Poet, journalist, and dissident. He graduated with a degree in journalism from Kyiv University in 1957. He worked for the regional newspapers. Symonenko began writing poetry while a student, but because of the harsh environment of Soviet censorship he published little. Only one collection of his poetry appeared during his lifetime, Silence and Thunder, 1962.

The Court Sections sat sternly at the table, Notes crouched in corners, carefully inclined, Quotations with fixed bayonets stared sharply At the defendant who was being tried. The circular peered through his glasses, The audience huddled close, Instructions leaped out ghostlike From the wise wires of the phones. The sections hissed — "the defendant is foreign!" The circular croaked — "she's not from here." The notes piped in — "was never heard of." The audience, shocked, screamed. The circular looked sternly at the court And re-established silent rapport. They executed the defendant right away — The sanctimonious clauses carried the day. In vain did the defendant swear Her innocence. It could not matter there. The court was logical and strict, In no known category did she fit — She was a new idea.

Схожі презентації

Категорії