Презентація на тему:

Multilingualism

Завантажити презентацію

Multilingualism

Завантажити презентаціюПрезентація по слайдам:

is the act of using, or promoting the use of, multiple languages, either by an individual speaker or by a community of speakers. Multilingualism

Multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. Multilingualism is becoming a social phenomenon governed by the needs of globalization and cultural openness. Multilingualism

A multilingual person is one who can communicate in more than one language, be it actively (through speaking, writing, or signing) or passively (through listening, reading, or perceiving). What is a multi-lingual person?

The terms bilingual and trilingual are used to describe comparable situations in which two or three languages are involved. A multilingual person is generally referred to as a polyglot. What is a multi-lingual person?

Poly (Greek: πολύς) means "many", glot (Greek: γλώττα) means "language". What is a multi-lingual person?

Multilingual speakers have acquired and maintained at least one language during childhood, first language (L1). The first language (the mother tongue) is acquired even without formal education. What is a multi-lingual person?

Children acquiring two languages are called simultaneous bilinguals. Take note! In the case of simultaneous bilinguals, one language usually dominates over the other. What is a multi-lingual person?

There is a possibility for a child to become naturally trilingual by having a mother and father with separate languages being brought up in a third language environment. What is a multi-lingual person?

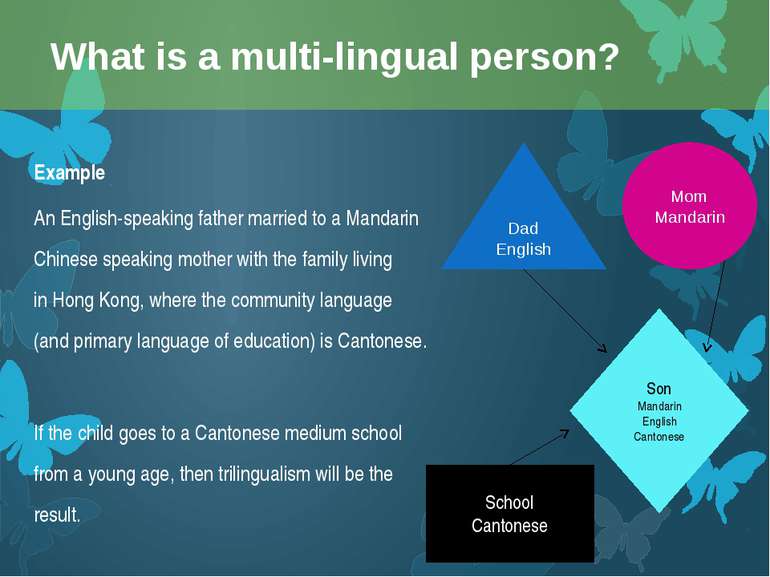

Example An English-speaking father married to a Mandarin Chinese speaking mother with the family living in Hong Kong, where the community language (and primary language of education) is Cantonese. If the child goes to a Cantonese medium school from a young age, then trilingualism will be the result. What is a multi-lingual person? Dad English Son Mandarin English Cantonese Mom Mandarin School Cantonese

Some group of academics argues for the maximal definition of multilingualism. Maximal: Speakers are as proficient in one language as they are in others and have as much knowledge of and control over one language as they have of the others. Varied Perspective of Multilingualism

Another group of academics argues for the minimal definition of multilingualism, based on use. Minimal: Tourists who can successfully communicate phrases and ideas even if not fluent in the native language of the foreign land can be considered as bilinguals. Varied Perspective of Multilingualism

Bilingualism as an individual attribute: a psychological state of an individual who has access to two language codes to serve communication purposes. Individual vs. Societal Multilingualism

Bilingualism as a societal attribute: two languages are used in a community and that a number of individuals can use two languages. Individual vs. Societal Multilingualism

“Even if someone is highly proficient in two or more languages, his or her so-called communicative competence or ability may not be as balanced” Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

Linguists have distinguished various types of multilingual competence, which can be put into two categories: Compound Bilinguals Coordinate Bilinguals Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

Compound Bilinguals words and phrases in different languages are with the same concepts. Example: 'chien' and 'dog' are two words for the same concept for a French-English speaker of this type. These speakers are usually fluent in both languages. Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

Coordinate Bilinguals Words and phrases in the speaker's mind are all related to their own unique concepts. Thus a bilingual speaker of this type has different associations for 'chien' and for 'dog‘. Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

In these individuals, one language, usually the first language, is more dominant than the other, and the first language may be used to think through the second language. Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

In these individuals, one language, usually the first language, is more dominant than the other, and the first language may be used to think through the second language. Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

A sub-group of the latter is the subordinate bilingual, which is typical of beginning second language learners. Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

Many theorists are now beginning to view bilingualism as a "spectrum or continuum of bilingualism" that runs from the relatively monolingual language learner to highly proficient bilingual speakers who function at high levels in both languages (Garland, 2007). Comparing Two Multilingual Speakers

When acquisition of the first language is interrupted and insufficient or unstructured language input follows from the second language, as sometimes happen with immigrant children, the speaker can end up with two languages both mastered below the monolingual standard. Cognitive Ability

Literacy plays an important role in the development of language in these immigrant children. Those who were literate in their first language before arriving, and who have support to maintain that literacy, are at the very least able to maintain and master their first language. Cognitive Ability

Receptive bilinguals are those who have the ability to understand a second language, but do not speak it. Receptive Bilingualism Receptive bilinguals may rapidly achieve oral fluency when placed in situations where they are required to speak the language.

Receptive bilingualism is not the same as mutual intelligibility, which is the case of a native Spanish speaker who is able to understand Portuguese, or vice versa, due to the high lexical and grammatical similarities between Spanish and Portuguese. Receptive Bilingualism

Widespread multilingualism is one form of language contact. Multilingualism was more common in the past. In early times, when most people were members of small language communities, it was necessary to know two or more languages necessary for trade. Multilingualism within Communities

When all speakers are multilingual, linguists classify the community according to the functional distribution of the languages involved: Diglossia Ambilingualism Bipart-lingualism Multilingualism within Communities

When all speakers are multilingual, linguists classify the community according to the functional distribution of the languages involved: Diglossia Ambilingualism Bipart-lingualism Multilingualism within Communities

Diglossia If there is a structural functional distribution of the languages involved, the society is termed 'diglossic'. Typical diglossic areas are those areas where a regional language is used in informal, usually oral, contexts, while the state language is used in more formal situations. Multilingualism within Communities

Ambilingualism a region is called ambilingual if this functional distribution is not observed. In a typical ambilingual area it is nearly impossible to predict which language will be used in a given setting. Multilingualism within Communities

Ambilingualism Example: Malaysia and Singapore, which fuses the cultures of Malays, China, and India. Multilingualism within Communities

Bipart-lingualism if more than one language can be heard in a small area, but the large majority of speakers are monolinguals, who have little contact with speakers from neighboring ethnic groups, an area is called 'bipart-lingual'. Multilingualism within Communities Serbia, Greece, Macedonia, Montenegro, Croatia, Bosnia, etc.

Some multilinguals use code-switching, a term that describes the process of 'swapping' between languages. In many cases, code-switching is motivated by the wish to express loyalty to more than one cultural group. Multilingualism Between Different Language Speakers

Sequential model In this model, learners receive literacy instruction in their native language until they acquire a "threshold" literacy proficiency. Some researchers use age 3 as the age when a child has basic communicative competence in L1 (Kessler, 1984). Multilingualism at a Linguistic Level: Models for Native Language Literacy Program

Sequential model In this model, learners receive literacy instruction in their native language until they acquire a "threshold" literacy proficiency. Some researchers use age 3 as the age when a child has basic communicative competence in L1 (Kessler, 1984). Multilingualism at a Linguistic Level: Models for Native Language Literacy Program

Bilingual model In this model, the native language and the community language are simultaneously taught. The advantage is literacy in two languages as the outcome. However, the teacher must be well-versed in both languages and also in techniques for teaching a second language. Multilingualism at a Linguistic Level: Models for Native Language Literacy Program

Coordinate model This model posits that equal time should be spent in separate instruction of the native language and of the community language. The native language class, however, focuses on basic literacy while the community language class focuses on listening and speaking skills. Multilingualism at a Linguistic Level: Models for Native Language Literacy Program

Cummins' research concluded that the development of competence in the native language serves as a foundation of proficiency that can be transposed to the second language — the common underlying proficiency hypothesis.

Early vs. Late bilinguals Early bilingual: someone who has acquired two languages early in childhood (usually received systematic training/learning of a second language before age 6). Late bilingual: someone who has become a bilingual later than childhood (after age 12).

Balanced vs. Dominant bilinguals Balanced bilingual: someone whose mastery of two languages is roughly equivalent. Dominant bilingual: someone with greater proficiency in one of his or her languages and uses it significantly more than the other language. Semilingual: someone with insufficient knowledge of either language.

Successive vs. Simultaneous bilinguals Successive bilingualism: Learning one language after already knowing another. This is the situation for all those who become bilingual as adults, as well as for many who became bilingual earlier in life. Sometimes also called consecutive bilingualism.

Successive vs. Simultaneous bilinguals Simultaneous bilingualism: Learning two languages as "first languages". That is, a person who is a simultaneous bilingual goes from speaking no languages at all directly to speaking two languages. Infants who are exposed to two languages from birth will become simultaneous bilinguals.

Successive vs. Simultaneous bilinguals Receptive bilingualism: Being able to understand two languages but express oneself in only one. This is generally not considered "true" bilingualism but is a fairly common situation.

Additive vs. Subtractive bilinguals Additive bilingual: The learning of a second language does not interfere with the learning of a first language. Both languages are well developed. Subtractive bilingual: The learning of the second language interferes with the learning of a first language. The second language replaces the first language.

Elite vs. Folk bilinguals Elite bilingual: Individuals who choose to have a bilingual home, often in order to enhance social status. Folk bilingual: Individuals who develop second language capacity under circumstances that are not often of their own choosing, and in conditions where the society does not value their native language.

Cummins' research concluded that the development of competence in the native language serves as a foundation of proficiency that can be transposed to the second language — the common underlying proficiency hypothesis.

Схожі презентації

Категорії